Why decentralized social services fail (so far)

Once in a while I read about another decentralized social network, full of great social ideas, strong privacy features, interesting cryptographic defenses against data misuse. The new underdog is typically on a mission to finally disrupt “centralized” social media platform as we know it, but in a nice fair way. Then it goes away into oblivion again.

Discussion around how these decentralized platforms fail almost always misses the reason “why”, focusing on the technical “how” instead.

I believe the “why” of these failures is not technical. It often feels like distributed and federated services provide better resiliency and privacy than typical star-topology systems. And “better” feels like “it should replace current solutions to the problem”, but in case of decenstralized social networks it’s just irrelevant.

Let’s try to figure out why.

Walled gardens are evil

(but most of us tend to live in one of them anyway)

Facebook et al. provide and maintain huge, single-point-of-entry, privately owned walled gardens with hostile privacy policies and yet they successfully serve billions of users, attracting some of the best engineering talent along the way. They are prone to privacy abuse and terrible data misuse, yet your mom doesn’t jump on blockchain-powered twitter clone.

Why is that?

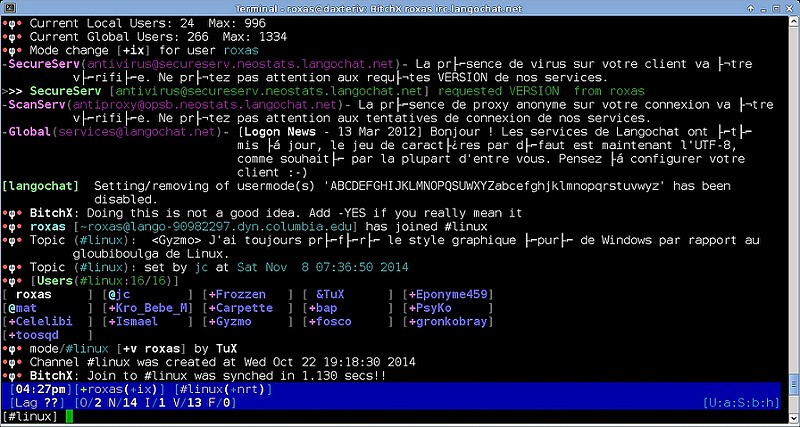

We’ve been gradually learning about building and maintaining better decentralized systems for half a century: e-mail, USENET, UUCP (bang address notation!), XMPP, IRC, running on top of decentralized protocols on every layer of communication — ARP, OSPF, BGP, etc.

But having better technology doesn’t mean you’re better at solving problems people have.

Incentives to build

I believe resiliency, security or public trust are 2nd order priorities for building a social network, and we’ll digress a bit to see why.

Television is an efficient medium for mass broadcasting, cinema is efficient medium for repeatedly earning revenue from once-staged performance.

Television didn’t kill the cinema, cinema didn’t kill theatre: there are still people attending both forms, then there’s much wider audience that is bound to a shiny TV screen. It’s not about the form, or the content that TV is transmitting. It’s all about the content consumption scheme and the incentive to build epic infrastructure for delivery: making a single node broadcast uniform data to a number of users, who are sitting on a couch and staring into the screen without having to make a conscious choice. It matches the lazy human behavior more, and it enables broadcast network to control and lead their attention - which can be sold. Still, some of avid TV consumers still go to cinemas, some of cinema-lovers still go to theatres as well. But the money is on TV.

With the Internet, we went through the same trajectory: Facebook didn’t kill LiveJournal, Jabber/ICQ didn’t kill IRC, Facebook messenger didn’t kill Jabber or Skype. But they made things repeatedly easier for users and wrapped them in a business model sufficiently profitable for the operator to constantly improve and seek new ways to lock people in.

Evolution of a service that is driven by incentive to keep your attention locked happens faster and more efficiently than decentralized system that has a hard time to agree on it’s spec improvement over a year. Simply because there’s a lot of money in keeping people’s attention, and there’s even more money in promising investors that the network operator will be capturing and selling visitor’s attention more efficiently down the line.

Is there any money in building decentralized social network? Is it sufficient to motivate a huge team of engineers to constantly improve it? Is there a central mission statement that allows engineers to quickly agree on design changes?

For Facebook, the challenge is “how to make it profitable and get away with the repercussions”. For decentralized social network, it is “how to make enough people join for this project to even make sense”.

Incentives to operate and maintain

Decentralization is hard to implement right, but its even harder to make network members keep it online, keep running decentralized network nodes a priority, consistently update code to stay compatible, and maintain it in coordinated fashion.

For Facebook, having it’s systems operational is directly tied to ads shown, DAU, and other metrics that impact profit. For our decentralized social network, the struggle is “how to incentivize everyone to form and maintain the basic network”.

When a node in a decentralized social network fails because of some serious technical issue that takes days to fix (because you don’t have enough engineers and every node failure can be unique to this very node), users will flee. If there’s no incentive for operator to operate or fix the node — sooner or later he’ll go ‘oh screw it’. So your mom tries the amazing decentralized experience and goes back to facebook.

The intuition behind “decentralized is good” comes from the way Internet itself is built. But there’s a good difference - if you operate an ISP and break BGP peering, you’re excommunicating yourself instantly, can’t provide services, and lose money or availability of your important assets. Because you don’t get to have responsibility of Internet routing ‘for fun and good social causes’. In some worst cases you excommunicate someone else and get booed by half of the Internet, but that’s another story.

But centralized infrastructure is much easier to maintain and control. Having a CDN, load balancing and request routing infrastructure at the front, then routing and managing properly redundant decoupled services in the back is a fine challenge.

Web is decentralized centralized protocol

(and we all want our stuff to happen in browser)

HTTP and surrounding protocols make great stack for border integration — point of simple compatibility between complex systems. For this purpose it’s quite efficient. Being a border integration protocol, HTTP enables building rich user experiences cost-efficiently.

However, by its very design, the Web incentivizes centralization as much as TV does.

Controlled, comfortable and predictable experience attracts users: millions surrender to the magic of the Apple ecosystem, where everything is well-thought and “seamlessly” integrated (at least if you don’t dig deep enough). Even in federated systems like the oldschool e-mail, in the “everything in browser era” few giants win by being able to endlessly iterate features and finally you end up exchanging 40% of your e-mail traffic with just a few large mail systems.

So, if we’re on the Web - we inevitably end up getting into a centralized system, with single entrypoint.

Then, after some time, the availability of your social graph starts to weigh in. If your less technically savvy friends and your mom, are on Facebook,— you either act as a luddite recluse, or you’re going to be on Facebook too, no matter how much you dislike it.

<Captain Obvious>

The attention of the audience in the walled harden is as easy to sell as TV. This is very practical — new medium, familiar business. No risk of iterating something completely new and not being able to sell it, easy to incentivize through the very design of the “new medium”, as we still call the decades-old Internet.

</Captain Obvious>

So, on one side you can attract more people, on the other you can sell them well enough to constantly improve the retention of their attention.

Incentives drive opportunities, not technologies.

Unfortunately for an engineering idealist, capital/impact distribution affects incentives and risk far more than privacy, resiliency and efficiency.

Most people will stay within current ecosystem, and will be absolutely fine supporting star topologies and walled gardens. Some, of course, will flee and create small closed communities around products and services that are decentralized. I suspect, these communities will be absolutely charming to participate in. And they will not survive long enough to matter. I’ve joined a few, because of social graph. But when they fall apart — somehow, I believe, we’ll catch up on Twitter anyway, to figure out where the next safe haven is.

And this leads to a my point.

Brilliant technical solutions are solutions to problems people want to solve, not the problems that we actually have. As soon as there will be a serious problem, which can be solved by decentralized or federated social service — it will be solved graciously, designs are well known already. Until then, we will adapt to the system that is bent towards incentives that are important right now.

Until we find the right incentives for distributed social networks to exist, they won’t.